Impact-driven networks – this is how philanthropy can ‘fund the glue’

Julia Gillard’s call to action was possibly the most oft-repeated at the Philanthropy Leadership Summit 2025. This Q&A with Darius Polok, Managing Director of the International Alumni Center (iac Berlin), who spoke at the event, delves into how philanthropy can invest in supporting the community networks and ecosystems necessary to achieve systems change. However, this will require shifts in perspective and practice.

The iac Berlin in Germany supports impact-driven networks and co-ordinates the Bosch Alumni Network – a multi-community network of 9,000 alumni and partners of the Robert Bosch Foundation. Darius is actively involved in coalition-building processes and advises social change actors on the design and implementation of networked approaches.

Giving News: What is an impact-oriented network as opposed to a community?

Darius Polok: In network theory, a community is a group of people or organisations connected through strong and trusted relationships. These ties create closeness, but they also carry the risk of becoming an echo chamber, where everyone sees the world in a similar way.

An impact-oriented network is made up of multiple communities connected through both strong and weaker ties, and involves a range of stakeholders in a more layered and orchestrated structure. It’s a relational setup that brings together different perspectives – communities, businesses, institutions, governments – and aligns them through the work of an orchestrator or network builder towards a shared purpose, often around improving standards or tackling common challenges.

Our belief is that no single actor can create the systemic changes needed to address today’s complex issues. These challenges require the combined effort of many actors, connected and co-ordinated within such an impact-oriented network.

GN: What’s the circular impact model and how can philanthropic entities invest in more effective networks related to their mission?

DP: While the classical ‘Impact, Outcome, Output, Input’ (IOOI) model describes impact as a linear cause-effect chain, the circular impact model builds on the idea that interventions in relational infrastructures – communities and networks – create ripple effects.

These reinforcing waves of knowledge, social capital and support expand beyond individual members and allow for deeper social impact. Put simply: a network is more than the sum of its parts. We need to observe carefully if and how the feedback loops are working. Very often, systems don’t have functioning flows – or they’re disrupted. At iac Berlin, we work with organisations to identify gaps and make the connections work again.

In the dominant model of philanthropy, interventions in the field are often not really seen as connected to a foundation’s own inner constitution. Calls to action, like the one from Julia Gillard, to also support the connecting organisations and groups in a community around a funded program, are usually understood as a push to improve programs. But in a connected world, the challenge is also internal: to prepare our own processes, structures and culture for the unforeseen effects of our interventions.

So, if a philanthropic entity wants to stay relevant, it has to stay in relationship with the field –open to changes, new information and disruptions coming from there. Part of the question is: are we ready to shift much more from short-term to long-term relationships? Are foundations willing to take on the role of supporting a field as a whole? From an ethical perspective, short-term funding simply does not lead to the systemic changes we want to see. It’s not just about supporting individual entities, it’s also about recognising the other actors in the field and asking: how do we connect to them, how do we support them too?

Some philanthropies in Europe – and I would guess in Australia – are working in this way, but many are still operating in the more traditional mode.

GN: How do you build and support impact-oriented networks?

DP: The two key roles to consider here are those of the orchestrator and the catalyst. A catalyst engages for a short time to strengthen the quality of relational infrastructure, while an orchestrator is committed for the long term and accepted by the field in that role. In most cases, it is not large philanthropic institutions but locally rooted organisations that are recognised as effective orchestrators.

Orchestrators are often most successful when they remain nearly invisible, giving the stage to other actors in the network or field. A critical question we raise when advising foundations is: Are you prepared to support these stewardship organisations and, through them, the resilience and sustainability of the entire ecosystem?

To support this work, we have developed diagnostic and network-mapping tools to identify existing actors, highlight missing connections and strengthen the flow of resources across a network. The quality of these connections is essential. In Europe, we observed that funding structures frequently push NGOs into competition with one another. If we want to build collaborative structures based on trust and strong relationships, we must consider whether a cultural shift from ‘ego to eco’ is possible, rather than forcing NGOs into survival mode.

With some partners, we explore ways of changing funding practices toward a more ecological model – one in which organisations are encouraged to collaborate and, at times, step back, recognising when it would be better for another to receive funding. In a healthy network, orchestrators play a vital role because they are close to the field and able to distribute resources more effectively than traditional funding mechanisms.

Community foundations are often excellent examples of such orchestrators or backbone organisations, as they connect different layers of the ecosystem – from individuals and community leaders to private companies and government.

GN: How can networks be an asset to tackling the complex challenges of the polycrisis?

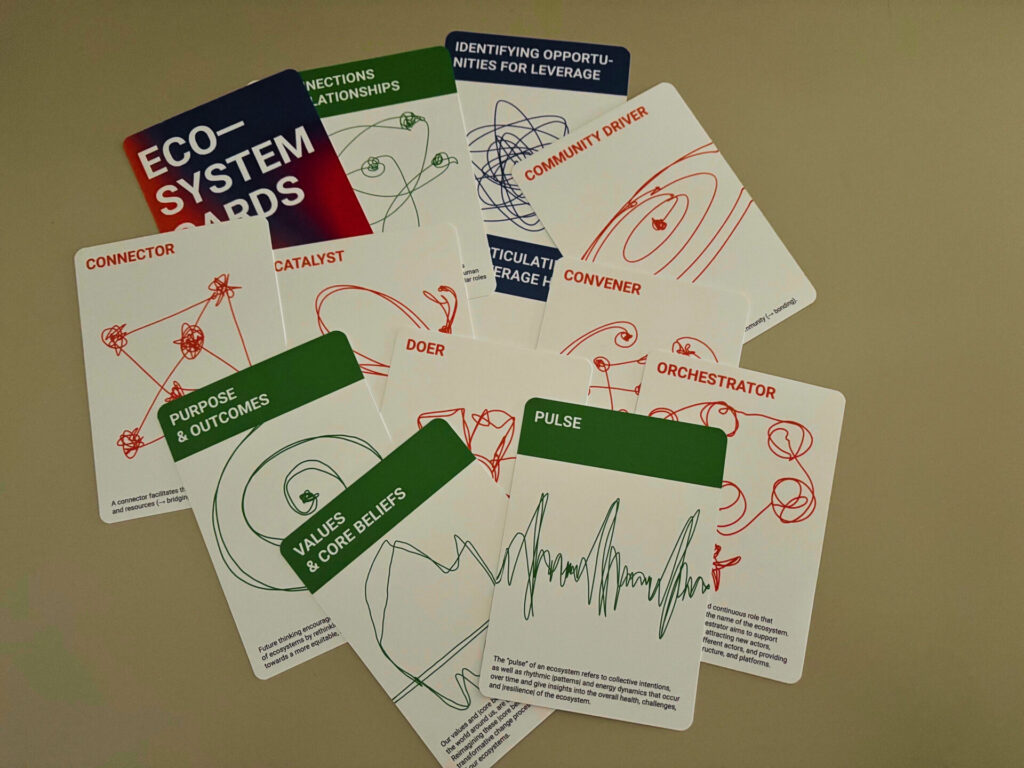

DP: Our approach to impact networks is ecosystemic. It’s not just about strengthening the connections, but also about building on shared values, collective narratives and a common orientation toward imaginative futures and emerging trends. One practical tool is the Ecosystem Cards set, which we brought to the Leadership Summit in a workshop with Community Foundations Australia.

Learn more about the Ecosystem cards here. Read about this Philanthropy Leadership Summit session here.

Since we cannot predict how systems will evolve or respond to our interventions, we need a new kind of leadership. We require more impact-network builders, but equally a leadership capacity tailored to complex ecosystems – one that is grounded in relationships and attuned to working with unforeseen change. Ecosystem leadership is an emerging practice and colleagues around the world are only beginning to explore what it can mean in their contexts.

GN: How can philanthropy in Australia develop this type of leadership for ecosystems?

DP: First, the capacity to deal with complexity and uncertainty is still not a priority when hiring in philanthropy. This means that this type of leadership is not yet what foundations expect from their teams. So one step is to change recruitment systems and bring people with these capacities into the core circles of philanthropy.

The second point is about how we see our futures – and I say futures in the plural, because they are always open and unpredictable. In Europe, there are discussions around foresight and imagination as a core capacity, and this is highly relevant for developing new forms of leadership. We need people who are ready, creative, open and able to hold the uncertainty of different futures.

The third issue concerns CEOs and boards. It is often at the executive level where support for this shift is missing. Expectations still revolve around predictable results, rather than an open, dialogical approach to leadership and complexity-informed approaches.

So how do we move forward? One important step is to communicate a fresh narrative – making the new paradigm that focuses on relational approaches visible, sharing practices and tools, and articulating why this shift is needed and what it could look like. That’s something we’re only beginning to do.

GN: Why are you passionate about this relational approach?

DP: Because we are in the middle of a profound global transformation. The shifts we see in philanthropy are a mirror of what is happening across society. Our systems and institutions may not withstand the coming disruptions, so the question is: how can we make them more resilient, and what will come after?

One assumption is we will need systems that are adaptable, flexible and open – systems that are ready to engage with complexity. Philanthropy has a unique responsibility. Unlike governments or the private sector, it has the freedom and the resources to help prepare our societies for this transition.

For me, philanthropy should be both: a trusting supporter of impact-oriented networks and their orchestrators, and an initiator and catalyst – a spark for the transformation we want to see.