Professor Thomas Homer-Dixon: How can we lead with ‘commanding hope’?

Globally renowned complex systems expert, Canadian Professor Thomas Homer-Dixon, kicked off the main event at the Philanthropy Leadership Summit 2025 by unpacking the polycrisis. Speaking to Giving News beforehand, he said that leadership for our times involves helping people to be more comfortable with uncertainty and understand that it ‘creates possibilities for novel breakthroughs’.

Professor Homer-Dixon is based at the Cascade Institute in British Columbia, Canada, an applied science thinktank. Its researchers take complexity science and use it to try to anticipate challenges and shocks that may hurt people around the world.

Giving News: Can you unpack what you mean by the polycrisis?

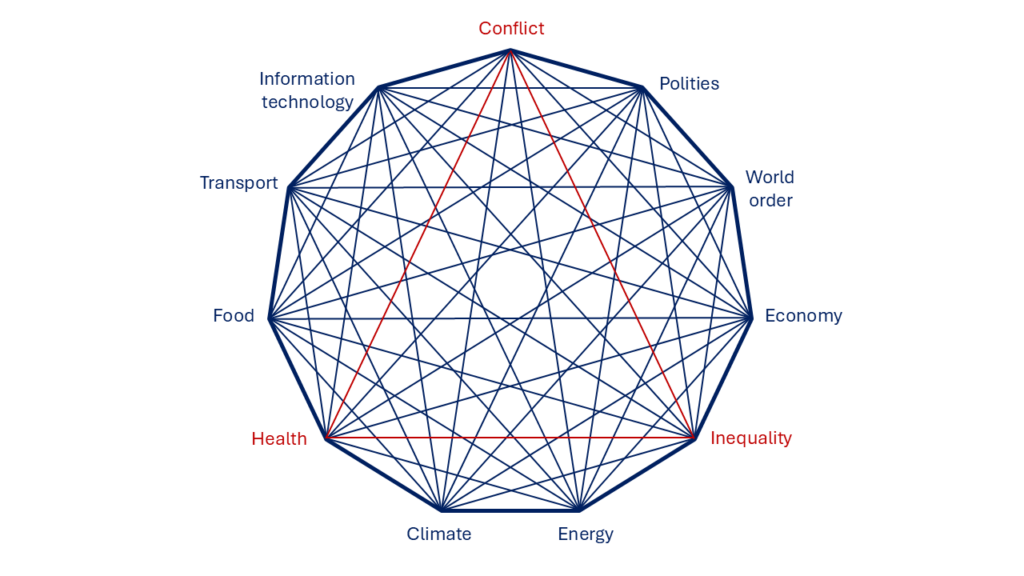

Professor Thomas Homer-Dixon: The polycrisis is basically a lot of bad stuff happening simultaneously in the world. The pandemic, climate shocks, extreme weather, war, geopolitical instability, mass migrations, the rise of populist authoritarianism and increasing political polarisation in societies.

These things are happening at the same time in ways that we don’t fully understand, and the frequency of these impacts is increasing and the magnitude of the damage they’re doing is increasing. The question then becomes, is this just a coincidence or are there some underlying causal dynamics that are linking things together? Our argument at the Cascade Institute is that there are underlying causal connections, and we’re trying to understand those better.

GN: What makes this different from other crises that the world has faced before?

This is a unique or sui generis situation for humanity. There are forces unfolding at a planetary level that humankind has never unleashed before. The most obvious is the change of the energy balance of the planet. There’s much more heat trapped on the planet’s surface than before. This is a macro change in the biosphere and circulatory systems of atmosphere and oceans that human beings have never produced before.

It’s also a function of the fact humankind is the largest concentration of genetically similar biomass on the planet now, which is a wonderful medium for the propagation of zoonotic viral diseases unlike any that have existed with previous pandemics. The unprecedented combination of high connectivity and homogenization in our food supply, institutional and financial systems increases the risk of cascading failures and systems of an unprecedented magnitude.

GN: In your book, Commanding Hope, you talk about hope not as a passive state but as an active, muscular response to the crises and that humanity is deluding itself about the extent of the challenges we face, therefore our response is not adequate. How should we be reframing it?

There’s a lot of wishful thinking out there about whether we’re going to be able to manage the climate situation and have the tech fixes to particular aspects of the challenges we’re facing. There’s also wishful thinking about the trajectory of populist authoritarianism and whether it’s just a temporary blip. Basically, we want to tell ourselves that it’s going be OK.

We need to acknowledge that actually it’s not OK. That doesn’t mean there’s no hope, but we need to start by recognizing the severity of the challenges we face. So, diagnosis proceeds prescription. If you’ve got a very serious disease, you want a doctor who gives an honest opinion, so you can focus all your efforts in the right place. What’s not healthy is hoping that the doctor will tell us it’s going be OK. But that’s what we’re doing when we elect leaders who are tell us, ‘We’ve got this problem, don’t worry about it’.

And actually each one of these problems is getting worse and worse, so the starting point is that we have to, as best we can, get an accurate understanding of the serious of our situation, what the probabilities are, and then can we identify an outcome that’s motivating.

GN: How are they synchronising, amplifying and accelerating?

Almost all of these stresses, because of the connectivity in the system and feedback loops. For example, fossil fuel consumption leading to climate change impacts that produces economic costs. As people feel less economically secure, they support authoritarian leaders, but that then leads to a backlash against green policies, undermining efforts to reduce fossil fuel consumption. That’s an example of a feedback loop, where the world gets trapped in a cycle that exacerbates the underlying problems.

The Cascade Institute is just about to publish the Polycrisis Core Model – a comprehensive analysis of all these stresses, which allows for some quantitative understanding of what the outcomes will be. It’s a big numerical model and projection of 10 or so possible futures to 2040.

Most of them are look pretty bad, basically societal collapse. But there’s one that does exist that’s very good, and its very existence is a big deal. It’s the most exciting finding we’ve had. The model is starting to show us what changes we need to make to find a pathway to that positive outcome.

GN: What role can philanthropy play?

We need to tell a narrative that gives us something to aim for in the future that’s positive, not scary. In Australia, my guess is that the transition to a zero-carbon economy, which will come in time, needs to be one that fits with Australian worldviews – and be made exciting to Australians.

Philanthropy can play a role in the deliberate development of narratives for societies that tell us how we can be in a good place – which is very different from where we are right now. That the future can be productive, it can be humane and prosperous, and people can be supported and have jobs. Philanthropy can play a role in this worldview evolution.

The last part of Commanding Hope is all about worldview transition. What are the stories Australians are telling themselves about what life will look like in 2100 or 2150 when the planet is three degrees warmer. How can they be positive stories?

GN: What kind of leadership do we need for our times?

THD: There’s huge premium on people who are honest with their constituents and with society, and there’s a hunger for that. Good leadership is saying, ‘We don’t know completely what’s going on here, but this is the best we know at the moment. We’re going to make this decision and do course corrections along the way as we learn more.’

Good leaders help their constituents be more comfortable with the uncertainty of our world and model the idea that the unknown is not always scary – it’s also the space where great hope and possibility lies.

Most importantly, leaders are going to have to help people manage their emotional reactions of fear and anger, so they don’t search for someone or a group to blame. They’ll need bring people together rather than divide them. This emotional management, working with people to help them manage their responses to the uncertainty and the surprise of the polycrisis is going be an essential component of leadership in the future.