Who were the two founding ‘godmothers’ of Philanthropy Australia?

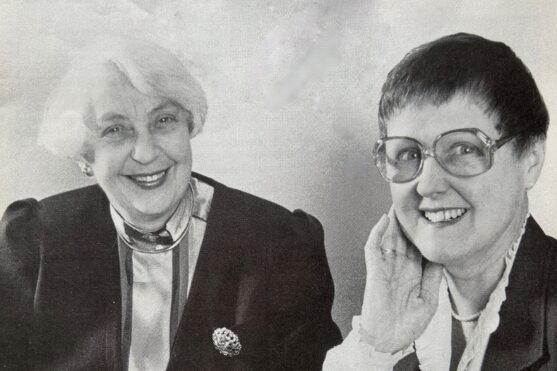

In this fascinating look back in time, we share an archival story about the two women founders of Philanthropy Australia, first known as the Australian Association of Philanthropy (AAP). This extracted article is taken from a 1989 edition of our newsletter at the time, called Philanthropy. Pat Feilman and Meriel Wilmot (pictured left-right) are introduced as ‘the two people most instrumental in setting up the association’. In the interviews, they reflect on the state of philanthropy at the time, why they wanted to establish an association of philanthropists – and the initial reluctance of many in the sector to be involved.

A note from the newsletter’s editor, Jane Sandilands, who carried out the interviews, says that the two women met in the early 1960s when Sir Ian Potter and Kenneth Myer AC DSC were involved in a project to gather funds to build what was then the Howard Florey Institute at the University of Melbourne.

Realising the benefits of a forum for the philanthropic sector, they organised two conferences, one in 1972, primarily to discuss the changes to the social structure being made by the Whitlam Government. The next conference in 1974, was the direct forerunner to the founding of the association in 1975.

As we approach the 50th anniversary of that conference this year, it’s a poignant opportunity to reflect on these two strong and inspiring women who were so instrumental in bringing the sector together on a professional footing. The article is simply headlined ‘The Godmothers’ and introduces Pat and Meriel as contributing ‘a wealth of knowledge and experience to philanthropy’.

The article has been edited for length. To read the full article and December 1989 edition of Philanthropy, visit our website.

Pat Feilman

Pat Feilman has been Executive Officer of The lan Potter Foundation for more than 25 years. Her interests cover a wide field, including being a member of the Zoological Board of Victoria, the Victorian Conservation Trust, the State Film Centre Council and The Tobacco Leaf Marketing Board.

How would you describe the state of philanthropy in Australia?

Philanthropy is a difficult idea to sell to people to get them interested. This country has a fairly poor track record in terms of private philanthropy, given the huge wealth that’s been accumulated in the last 20 years.

Why do you think this is so?

It’s difficult to say. I suppose we don’t have the same sort of culture they had in the early part of the century in the US, where the tremendous blossoming of philanthropy took place. Perhaps there aren’t the same needs for it – that’s the other point. We think we have a lot of needs, but we’re a pretty affluent society really and the welfare system does give a fair bit, so I suppose it’s a question of perceived needs.

Does funding depend to a large degree on the interpretation of the charter of a trust or foundation?

Yes, I suppose. Education, for example, is a very broad field – long as a piece of string really. Nobody could have guaranteed the groundswell after the Farmland Project, or even that it would succeed anyway. There were huge possibilities that it wouldn’t. There are great risks in trying to make it happen. That really is what foundations ought to be about: a bit of risk-taking. What’s the point of just going in and backing something that someone else says is great? If it’s not chancy and it’s good, it ought to be being backed by government anyway.

Is there a key to success for projects chosen for funding?

Success or otherwise really revolves around the people. You can have the best project in the world, but if you can’t get good people to run it, it won’t work. The strength of our foundation is the diversity of its board. Each person has their own network, their own field of expertise. They are people with very high integrity, able to rise above their institutions and able to look objectively at proposals. Working with people for whom I have such great respect – and the success of the some of our important projects – have made the last 25 years immensely worthwhile for me.

Meriel Wilmot

Meriel Wilmot is widely known in the philanthropic community. She was the first Executive Officer of The Myer Foundation, taking up her appointment in 1961, a position that she held until 1982. In her other life, she is Lady Wright, wife of the retiring Chancellor of the University of Melbourne, Professor Sir Douglas Wright.

How did you first become involved in the philanthropic area?

When I went to England in the early 1950s, I had four or five introductions, one of which was to the Nuffield Foundation. Though initially I worked with the Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust, I moved to the Foundation itself a year later and saw the grantmaking processes and the way in which a foundation can bring about changes in a community. I suddenly realised the importance of this huge industry, the existence of which I’d never known before.

How do you see the development of the philanthropic sector in Australia today, compared with a few years ago?

Ten or even eight years ago, it was very much an individualistic performance, with everyone playing their cards extremely close to their chests. That’s why it was difficult to get trusts to go into the Directory (of Philanthropic Trusts) for example, or to come into the Association (Australian Association of Philanthropy). They all wanted to do their own thing, believing they knew exactly how it should be done.

That’s changing now. It has certainly changed with regard to perhaps the 10 major trusts, which are far more prepared to co-operate and to look at philanthropy as a profession as well as an industry, but there’s a very long way to go with the vast majority of the smaller trusts.

Could you define the ‘profession’ of philanthropy?

I believe it to be the intention of collecting information about the community and understanding the community so that when people come to you for funds, you can measure their request against what you know from your own research. You therefore make an informed decision. It also means you can go out into the community and initiate work instead of just sitting there and waiting for people to come to you. A lot of this is dependent upon what staff you have – the numbers and their training. A lot of the smaller trusts don’t employ a full-time person. There are still trusts that have a set list of recipients that they tick off once a year.

Do you feel that the people employed by a trust or foundation, especially the Executive Officer, need to have extraordinary qualities?

Extraordinary – that’s too extreme. They need to be well-informed and I was extremely fortunate in that I had the chance of being trained in a world-class foundation. Secondly, in 1976 when I went to America to do a study of corporate philanthropy, I had hands-on experience (to use the current terminology) of seeing how grants were made.

When you and Pat Feilman talked in the early 1970s about the possibility of an association of philanthropy, what was the thinking behind that?

The main reasons, apart from talking to one another, is to improve the quality of giving. At the time, three or four trusts were meeting on a regular basis, considering applications and it was felt that this was very beneficial, leading to more professional philanthropy.

The recent conference pointed to the difficulty that grantseekers sometimes have in getting information about trusts and foundations. Why do you think that is?

Basically, I suppose if people know I’ve got money to give away, they’re going to ask me for it. I think this is why so many trusts and foundations refuse to go into the Directory. And they’re still knocking us back. Marion Webster (Executive Director of AAP) is receiving letters from people not just saying they don’t want to be included, but saying ‘how did you find my name in the first place – and please don’t write to us ever again’. These trustees fail to appreciate that once they receive the benefit of tax deductibility for their philanthropy, the money ceases to be private money – it becomes public money.

What do you feel about the future of the association?

I’m certainly hopeful about it having a very positive role. At the moment, it is being funded privately by various trusts and foundations that I believe are both generous and farsighted. Of course, the real future of the association is its strength as a lobby group. It needs to be a strong, united body.

Is there any particular time with The Myer Foundation that you regard as a highlight?

Overall, it was an extremely satisfying time for me. I was always interested in learning, finding out new things – I didn’t like not knowing what was going on around me and my work with the Foundation allowed me to find out new things all the time. I remember at one stage there was an application on my desk from the Australian Ballet School and another for the eradication of cattle tick in Queensland and I thought how lucky I was to have such a varied job! And yes, they both got a grant.

Read how Meriel was still giving at 100 years old to the Australian Communities Foundation.